The UNIC website uses cookies to improve your experience. Read our full Cookie Policy here.

The Blegny mine site on a sunny day.

The UNIC delegation is ready to go underground.

We were honored to have Jan van Bogget, a former coal miner in Blegny, as our tour guide. After equipping ourselves with miner’s jackets and safety helmets we headed to the elevator together. The miners call these elevators “cage”. There are two cages in operation at Blegny, where one works as a counterweight for the other. When the mine was still in operation the cages travelled up and down at a speed of 40 km/h. The mine shaft in Blegny was 600 metres deep and the coal that was mined there was considered to be of the best quality in Belgium. The so-called mine galleries (horizontal tunnels) were up to 5 kilometres long in Blegny. The miners worked in three shifts under very harsh conditions – day and night. They extracted about 1000 tons of coal every day, when the mine was still operational, Jan told us.

Our guide Jan van Bogget shows us a damp spot in the rocks where little drops of water slowly seep through.

Water was one of the biggest problems in this region in mines, because there was roughly eighty times more water than coal in the ground and a very high humidity. Yes, you read that correctly: 80 times more water than coal! So, the huge pumps had to run constantly day and night. Today, the deepest level of the mine is about 110 metres below the ground. All the levels below are flooded, because the pumps were stopped, when the mine was closed down in 1980.

The iron frames that hold the weight of the surrounding ground. There is a typical mining wagon in the background.

Special frames were constructed to sustain the rock. The risk of inundation and flash floods into the mine shafts was an ever-present danger for the miners, especially in this region, because of the large amount of water. As Jan pointed out, the most horrible mining accident in Belgium occured on 8th August 1956 in Bois du Cazier near Charleroi, where 262 men died during a fire in the mine, including a large number of Italian labourers. The mining safety regulations were revised all across Europe and a Mines Safety Commission was established in the aftermath of this disaster, but the Italian immigration of mine workers and their families to Belgium practically stopped in an instant.

Tokens of friendship between the miners from Blegny and various other European regions.

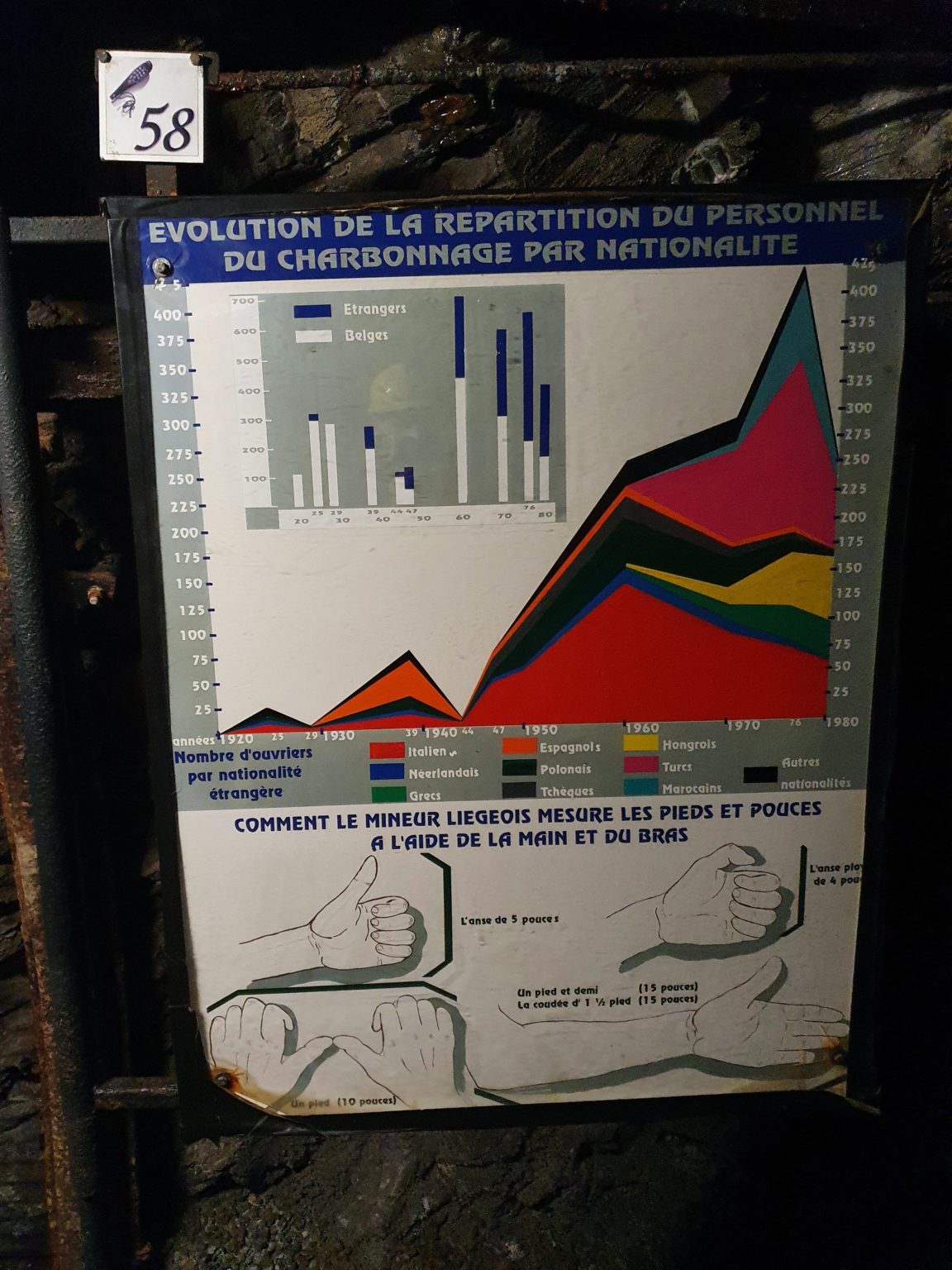

Our guide Jan van Bogget underlined the enormous friendship, companionship and solidarity between coal miners from all over the world. In Blegny, 14 different nationalities worked together at the mine site, relying on each other in very dangerous conditions. Only a third of the miners in Blegny were originally from Belgium. There were many Italians working in Blegny. When the Italian immigration to Belgium was significantly reduced after the Charleroi mining disaster of 1956, mostly people from Turkey, Morocco, Spain, Poland and other countries immigrated to Belgium to join the workforce in Blegny. Most of the miners in this region spoke the Walloon dialect.

An overview of the miners’ origins in the Liège region (top) and a depiction of improvised measurements with the help of fingers, hands and arms (bottom).

Davy lamps as a firedamp detector explained on the left and a winch on the right.

Carbon monoxide and other gases like methane were often a cause of death in the mineshafts, as well. In 1815, the English chemist Sir Humphry Davy invented the “Davy lamp”, a breakthrough innovation to reduce the danger of explosions in coal mines. Methane and other flammable gases that occured in the mines, called firedamp, couldn’t be smelled and the use of the infamous “canary bird in the coal mine” as a living firedamp detector wasn’t very efficient. With a Davy lamp you could detect firedamp by checking the colour and size of the flame that was behind an iron mesh screen. If the flame of the wick light turned green, there were flammable gases present.

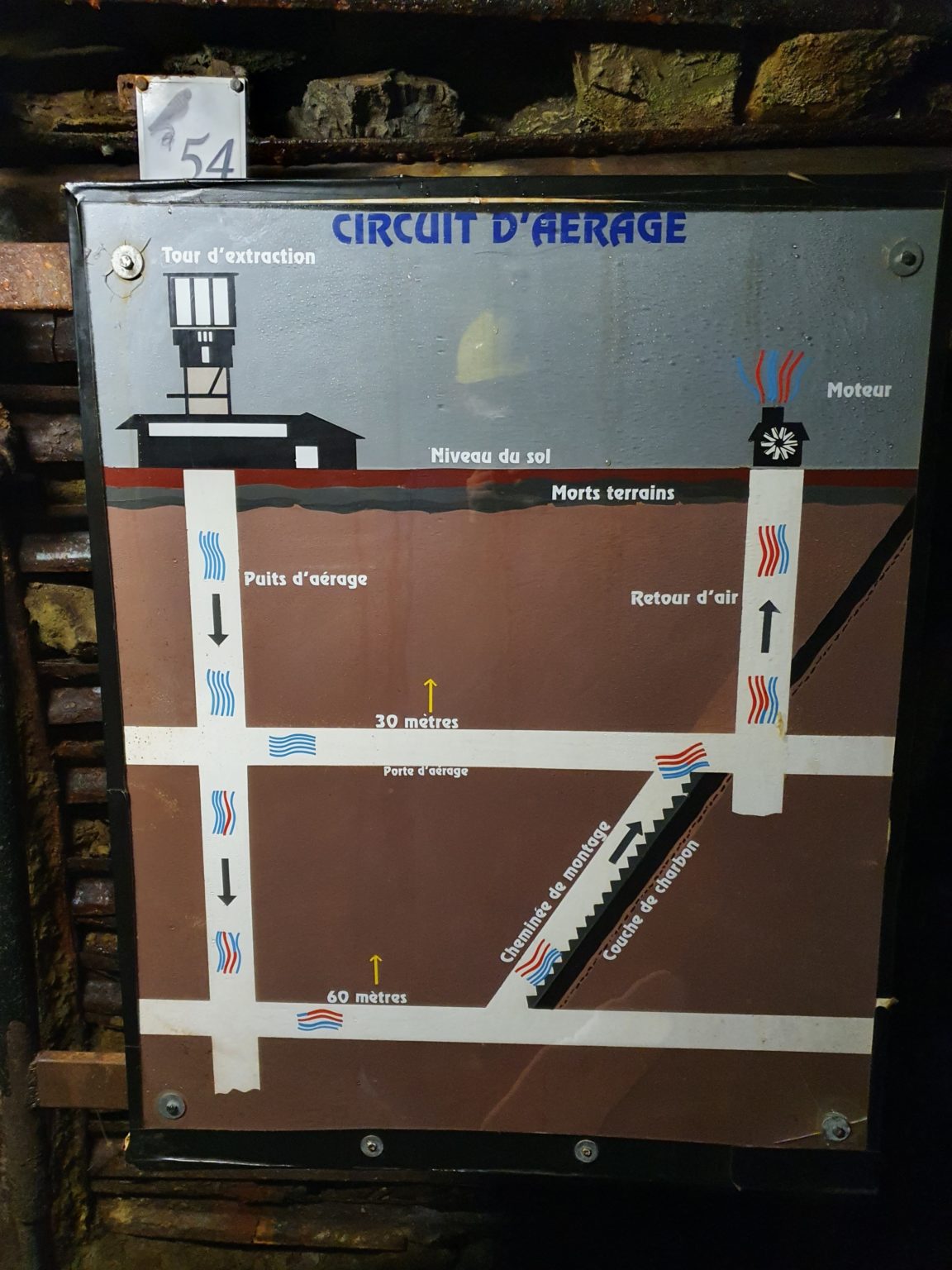

The airflow in the Blegny coal mine today.

Air circulation is another problem in mines. In Blegny, there was a big fan to vent the air from the mine, so that fresh air flows down the main shaft to the different levels of the mine. There were air gates installed between the different sections, which had to remain closed to provide a constant airflow. Today, they work with a much smaller fan in Blegny. The air usually follows the galleries, but the areas next to the coal seams where the miners are working have to be ventilated, as well. That’s why modern underground mines have extra ventilation systems.

Our guide Jan shows us an assortment of the most common miner’s tools.

Our guide Jan shows us an assortment of the most common miner’s tools.

Up until the end of the 19th century, women and children from 4, 6 or 8 years old were working in the mines, at least 12 to 14 hours a day. Later, it was forbidden by law to work inside the mines at such a young age. After 1880 no women and children were allowed to work in the coal mines underground. The minimum required age for children that worked above ground at the mine site was raised from 12 to 14 and later 16 years. Dust, humidity, darkness, noise and high temperatures were the common working conditions in the coal mines and 80% of mining accidents happened in the coal seams, where the space was very tight. As you can see in the picture, the slopes in the region are very high, while in Limburg, for example, the coal lines are almost flat and bigger. Originally, the coal layers were horizontal near Liège, as well, when they formed during the Carboniferous geological period roughly between 359 and 299 million years before our time. Because of the continental drift most of those horizontal layers shifted until they had a very high slope in this region, some of them being almost vertical. Every ten metres, there was one miner working in the steep coal seams of Blegny.

Coal seams were very tight, noisy, hot and dusty spaces.

The same coal seam from above.

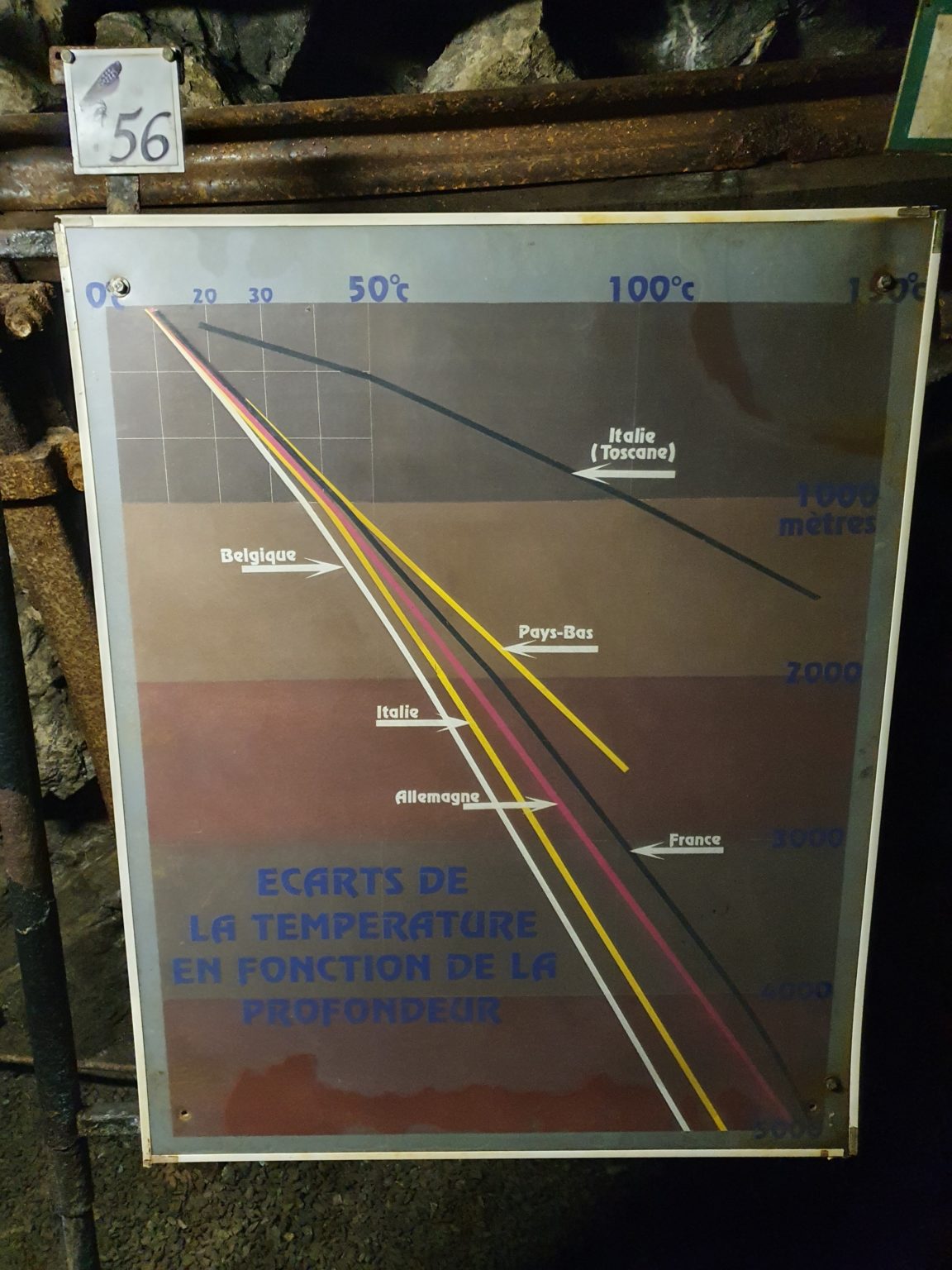

An overview of average temperatures in different depths in various European coal mining regions.

In Blegny, the average temperature in the galleries was around 32°C, while in Flanders it is 40°C at 1000 metres underground. Our guide Jan pointed out that the huge amount of water between the rocks in this region acts like a fridge and cools the temperature down. Though this may sound rather comfortable compared to the higher temperatures in other mining areas, you always had to be aware of the presence of water as a miner, especially when using large drills and other heavy machinery.

All the way down, we go. When the coal mine was still operational, there were no comfortable stairs and railings, of course.

A large drill.

A compressed air tank.

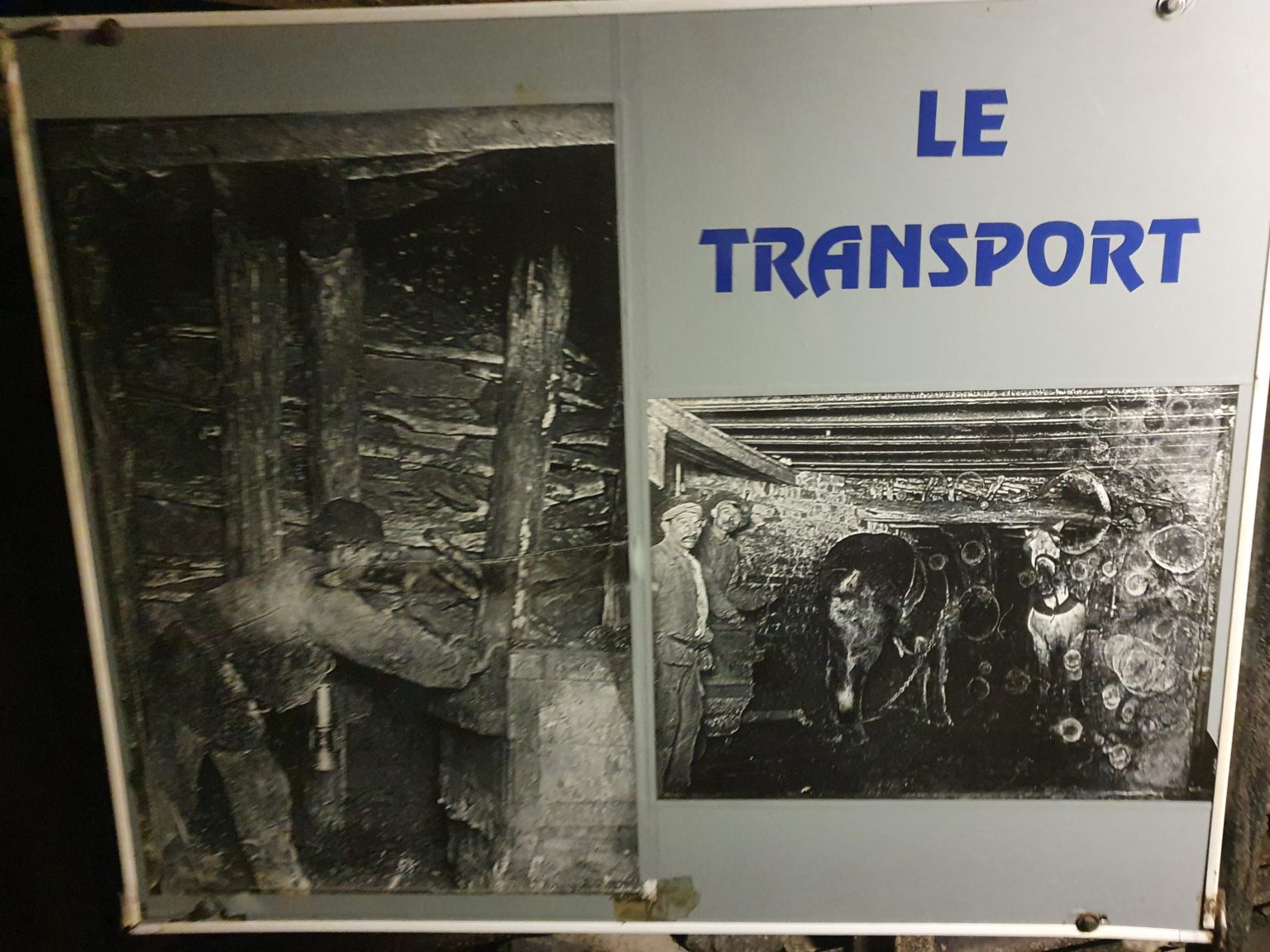

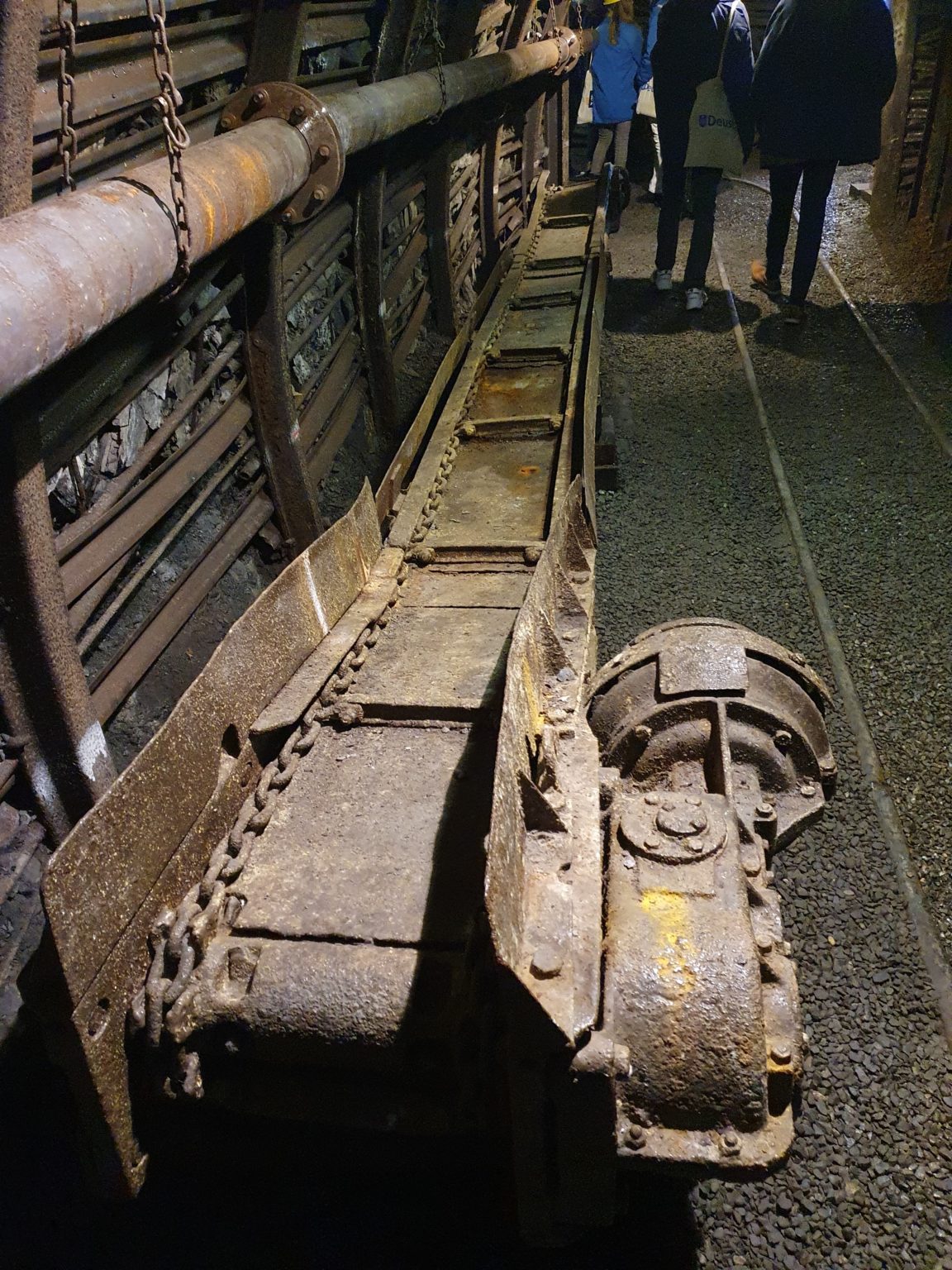

There were a lot of different jobs in underground coal mining. In Blegny, they had experts for the use of drills and dynamite, who pushed the shafts forward, while their fellow miners gathered rocks, loaded wagons and set up props and beams. Props to support the weight of the surrounding ground and rocks were made out of iron and wood. Only coniferous wood was used for props, because it creaks, when there is too much pressure on it. So wooden props out of coniferous wood had an integrated natural warning system for the miners. Carpentry was a very important trade for the operation of the mines. The wooden props were prepared in the woodworking shop above ground directly at the mine site. Compressed air was the safest energy in the mines because of explosion danger. Electricity was also used. In Blegny, there were locomotives, and even 30 work-horses to pull the wagons. They had two stables for the horses underground. Our guide Jan told us that those work-horses were underground for an average of 15 years and were almost blind mostly. Their hard work was highly valued and good people concerned about the well-being of the animals started a petition to augment the living conditions of the work-horses, which was granted. After that, the horses would slowly be transported in and out of the mine in special harnesses and with blinders on, so that they didn’t get anxious and couldn’t hurt themselves on the way up or down. The work-horses would then be on a pasture or in a stable above ground during the weekend. Later, the miners in Blegny also had conveyors to transport the rock, slate and coal.

The transport underground by hand and with horses.

A conveyor.

The driver’s cabin of a locomotive.

Wagons in the extraction tower.

The other side of the extraction tower.

Several transport carts and the gangway in the extraction tower on the right.

This machine turns the wagons upside down, so that the smaller rocks, slack and coal drop on a metal mesh with 80 mm holes below for sorting.

In this hall, the coal was sorted.

Here you can see different sizes of coal pieces. The slack (fine coal dust) was also gathered and formed into briquettes, which were mostly egg-shaped.

This statue depicts St. Barbara, the saint of all miners, firemen, artillerymen and other professions that seek protection from fire or explosions.

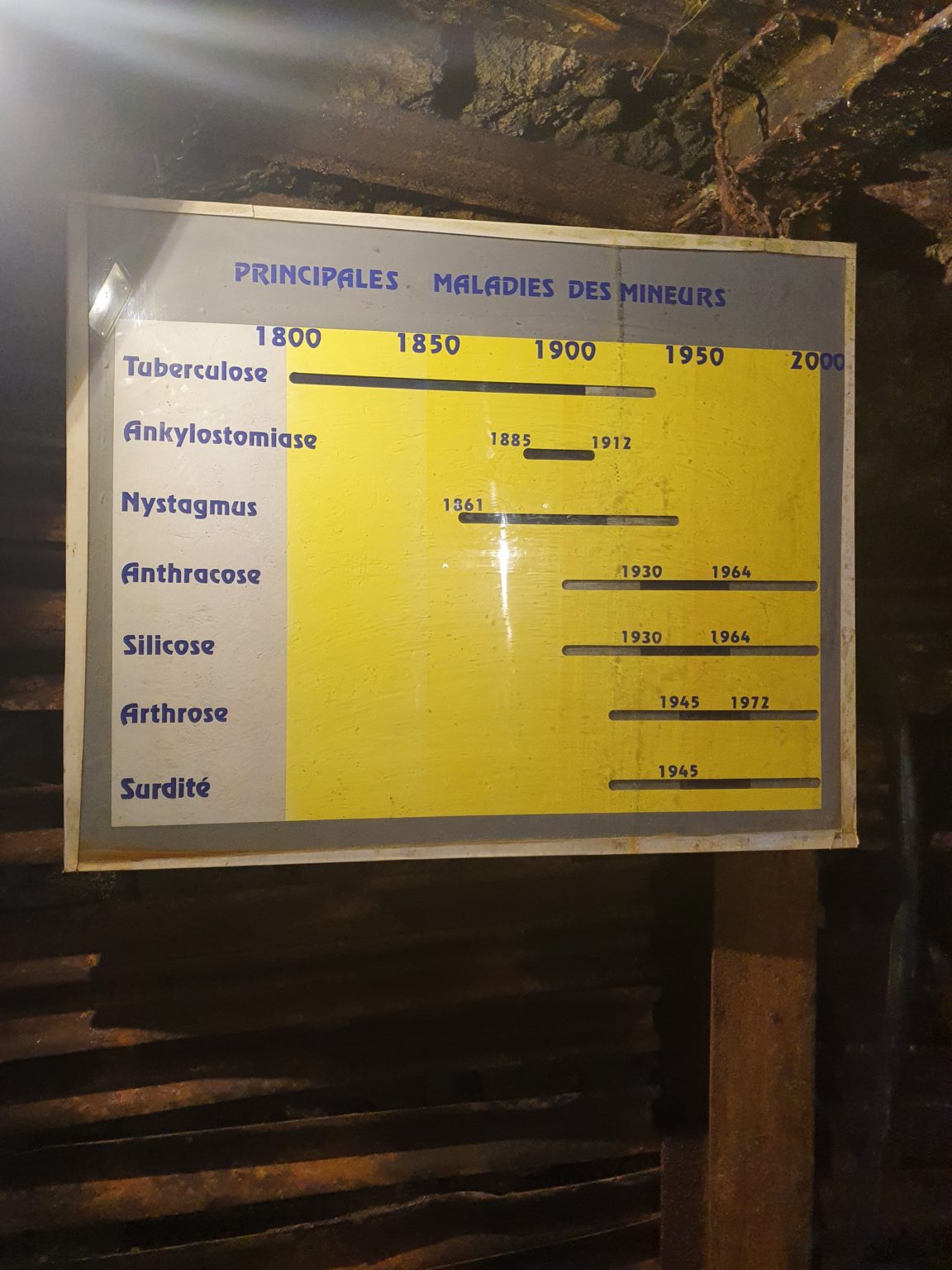

As we have learnt, not only flammable or toxic gases, flash floods, rockslides and explosions posed a threat to the miners’ and the work-horses’ life. Many severe diseases and ailments were part of the harsh and unforgiving working conditions underground. Partial or total deafness occurred due to the long-term exposure to loud noise. According to our guide Jan, Silicosis (an illness caused by the inhalation of fine silica dust particles) and coal worker’s pneumoconiosis (CWP or “black lung”) were the most dangerous diseases that cost many lives. Nystagmus (an involuntary rhythmic side-to-side, up and down or circular motion of the eyes) was quite common in earlier times, but it disappeared with the invention of better mining lamps.

A list of the most common diseases and ailments that miners were diagnosed with.

The transport of coal above ground to store and sell the highly demanded resource was also an important part of the coal mining industry and Liège’s Industrial Heritage as a whole. We shall never forget the thousands of brave and hard-working miners that have valued companionship, trusted each other with their lives and were exemplars of resilience who have contributed to the economic rise of whole regions.

Means of coal transport above ground: From horse carriages…

… to locomotives.

Gordon Rumley (University College Cork): “I have never been to a coal mine site before or anything similar to that. We got a feeling for the working conditions, the noise and the real danger the miners were in at every moment, so it was truly an eye-opening experience for all of us. It is such a fundamental part of modern history, but at the same time it’s quite upsetting to see what people had to go through and what people were required to do out of necessity – just to be able to live. You get a huge respect for the individuals and what they had to do – and how that has contributed to the society we live in today.”

Perrine Melen (University of Liège): “I found it very engaging and interesting, because I live here in Liège and little did I know about this place. It was really a surprise for me and I wasn’t prepared to learn so much in such a short time. I was aware of parts of the industrial history of Liège, but I never went to the Blegny mine site before. It is not the same when you read about history compared to when you see it in a realistic setting. So, the trip was really cool!”

Brian McCarthy (University College Cork): “It was good to engage in an event where you really get a full experience of what being a miner was like and how oppressive it was in terms of space and the noise in the mine, as well. This tour was very interesting in the context of post-industrial cities, as it was a shutdown mine, so an industry that has gone away. It was quite a dangerous industry to be involved in. Overall the tour was a great experience and I recommend going to Blegny and getting a feeling for how it was like in a coal mine.”

Daria Zaikovskaia (University of Oulu): “I liked this trip very much. I think that we take a lot of things for granted. For example, when we turn on the light, we don’t think about where the energy for this comes from. The walk in the mine made me recognize all the hard work, sacrifices and hardships the miners endured to bring us warmth, energy and to get a hold of the resources we needed to have. The path that we walked today was really emotional and moving, I feel like I learned something today. I think that not all the museums need to bring you joy – some need to really make you reflect. We should not forget our history while moving forward and I feel reminded of that today.”

By Philipp Dorok

Call for Submissions: UNIC Thematic Lines CityLabs Award 2026

Deadline: 16 March 2026 (23:59 CEST)

06 Jan 2026

Read more »RUB Centre for City Futures opens in Bochum, Germany

The UNIC Centre for City Futures (CCF) is a change agency bringing universities and cities tog...

18 Dec 2025

Read more »Interview: "It's a simple concept but powerful"

Fresh from the UNIC working conference in Bilbao, Maaike van Gerven, International Partnership...

16 Dec 2025

Read more »